In Victorian London, two children with mysterious powers are hunted by a figure of darkness—a man made of smoke.

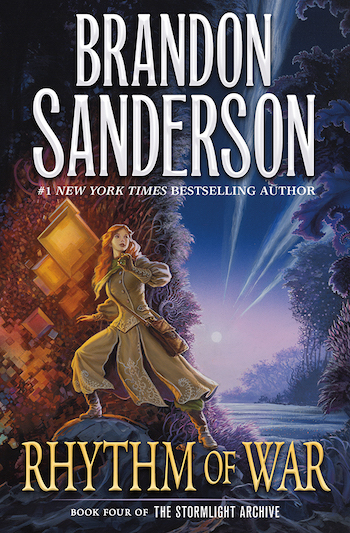

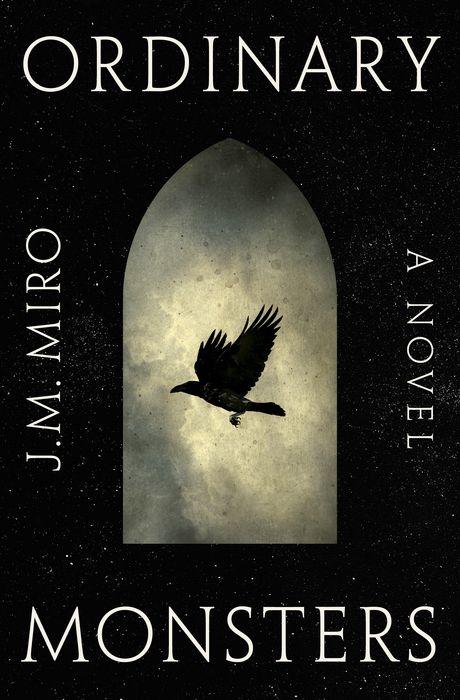

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt—both audio and text—from brand new historical fantasy Ordinary Monsters by J. M. Miro, available now from Flatiron Books and Macmillan Audio.

England, 1882. In Victorian London, two children with mysterious powers are hunted by a figure of darkness—a man made of smoke.

Sixteen-year-old Charlie Ovid, despite a brutal childhood in Mississippi, doesn’t have a scar on him. His body heals itself, whether he wants it to or not. Marlowe, a foundling from a railway freight car, shines with a strange bluish light. He can melt or mend flesh. When Alice Quicke, a jaded detective with her own troubled past, is recruited to escort them to safety, all three begin a journey into the nature of difference and belonging, and the shadowy edges of the monstrous.

What follows is a story of wonder and betrayal, from the gaslit streets of London, and the wooden theaters of Meiji-era Tokyo, to an eerie estate outside Edinburgh where other children with gifts—like Komako, a witch-child and twister of dust, and Ribs, a girl who cloaks herself in invisibility—are forced to combat the forces that threaten their safety. There, the world of the dead and the world of the living threaten to collide. And as secrets within the Institute unfurl, Komako, Marlowe, Charlie, Ribs, and the rest of the talents will discover the truth about their abilities, and the nature of what is stalking them: that the worst monsters sometimes come bearing the sweetest gifts.

The first time Eliza Grey laid eyes on the baby was at dusk in a slow-moving boxcar on a rain-swept stretch of the line three miles west of Bury St Edmunds, in Suffolk, England. She was sixteen years old, unlettered, unworldly, with eyes dark as the rain, hungry because she had not eaten since the night before last, coatless and hatless because she had fled in the dark without thinking where she could run to or what she might do next. Her throat still bore the marks of her employer’s thumbs, her ribs the bruises from his boots. In her belly grew his baby, though she did not know it yet. She had left him for dead in his nightshirt with a hairpin standing out of his eye.

She’d been running ever since. When she came stumbling out of the trees and glimpsed across the darkening field the freight train’s approach she didn’t think she could make it. But then somehow she was clambering the fence, somehow she was wading through the watery field, the freezing rain cutting sidelong into her, and then the greasy mud of the embankment was heavy and smearing her skirts as she fell, and slid back, and frantically clawed her way forward again.

That was when she heard the dogs. She saw the riders appear out of the trees, figures of darkness, one after another after another, single file behind the fence line, the black dogs loose and barking and hurtling out ahead. She saw the men kick their horses into a gallop, and when she grabbed the handle of the boxcar and with the last of her strength swung herself up, and in, she heard the report of a rifle, and something sparked stinging past her face, and she turned and saw the rider with the top hat, the dead man’s terrifying father, standing in his stirrups and lifting the rifle again to take aim and she rolled desperately in the straw away from the door and lay panting in the gloom as the train gathered speed.

She must have slept. When she came to, her hair lay plastered along her neck, the floor of the boxcar rattled and thrumped under her, rain was blowing in through the open siding. She could just make out the walls of lashed crates, stamped with Greene King labels, and a wooden pallet overturned in the straw.

There was something else, some kind of light left burning just out of sight, faint, the stark blue of sheet lightning, but when she crawled over she saw it was not a light at all. It was a baby, a little baby boy, glowing in the straw.

All her life she would remember that moment. How the baby’s face flickered, a translucent blue, as if a lantern burned in its skin. The map of veins in its cheeks and arms and throat.

She crawled closer.

Next to the baby lay its black-haired mother, dead.

***

What governs a life, if not chance?

Eliza watched the glow in the little creature’s skin slowly seep away, vanish. In that moment what she had been and what she would become stretched out before her and behind her in a single long continuous line. She crouched on her hands and knees in the straw, swaying with the boxcar, feeling her heart slow, and she might almost have thought she had dreamed it, that blue shining, might almost have thought the afterglow in her eyelids was just tiredness and fear and the ache of a fugitive life opening out in front of her. Almost.

Buy the Book

Ordinary Monsters

“Oh, what are you, little one?” she murmured. “Where did you come from?”

She was herself not special, not clever. She was small like a bird, with a narrow pinched face and too-big eyes and hair as brown and coarse as dry grass. She knew she didn’t matter, had been told it since she was a little girl. If her soul belonged to Jesus in the next world, in this one her flesh belonged to any who would feed it, clothe it, shelter it. That was just the world as it was. But as the cold rain clattered and rushed past the open railway siding, and she held the baby close, exhaustion opening in front of her like a door into the dark, she was surprised by what she felt, how sudden it was, how uncomplicated and fierce. It felt like anger and was defiant like anger, but it was not anger. She had never in her life held anything so helpless and so unready for the world. She started to cry. She was crying for the baby and crying for herself and for what she could not undo, and after a time, when she was all cried out, she just held the baby and stared out at the rain.

Eliza Mackenzie Grey. That was her name, she whispered to the baby, over and over, as if it were a secret. She did not add: Mackenzie because of my father, a good man taken by the Lord too soon. She did not say: Grey because of who my mama married after, a man big as my da, handsome like the devil with a fiddle, who talked sweet in a way Mama thought she liked but who wasn’t the same as his words. That man’s charm had faded into drink only weeks after the wedding night until bottles rolled underfoot in their miserable tenement up north in Leicester and he’d taken to handling Eliza roughly in the mornings in a way she, still just a girl, did not understand, and which hurt her and made her feel ashamed. When she was sold out as a domestic at the age of thirteen, it was her mother who did the selling, her mother who sent her to the agency, dry-eyed, white-lipped like death, anything to get her away from that man.

And now this other man—her employer, scion of a sugar family, with his fine waistcoats and his pocket watches and his manicured whiskers, who had called her to his study and asked her name, though she had worked at the house two years already by then, and who knocked softly at her room two nights ago holding a candle in its dish, entering softly and closing the door behind him before she could get out of bed, before she could even ask what was the matter—now he lay dead, miles away, on the floor of her room in a mess of black blood.

Dead by her own hand.

In the east the sky began to pale. When the baby started to cry from hunger, Eliza took out the only food she had, a crust of bread in a handkerchief, and she chewed a tiny piece to mush and then passed it to the baby. It sucked at it hungrily, eyes wide and watching hers the while. Its skin was so pale, she could see the blue veins underneath. Then she crawled over and took from the dead mother’s petticoat a small bundle of pound notes and a little purse of coins and laboriously she unsleeved and rolled the mother from her outerwear. A leather cord lay at her throat, with two heavy black keys on it. Those Eliza did not bother with. The mauve skirts were long and she had to fold up the waist for the fit and she mumbled a prayer for the dead when she was done. The dead woman was soft, full-figured, everything Eliza was not, with thick black hair, but there were scars over her breasts and ribs, grooved and bubbled, not like burns and not like a pox, more like the flesh had melted and frozen like that, and Eliza didn’t like to imagine what had caused them.

The new clothes were softer than her own had been, finer. In the early light, when the freight engine slowed at the little crossings, she jumped off with the baby in her arms and she walked back up the tracks to the first platform she came to. That was a village called Marlowe, and because it was as good a name as any, she named the baby Marlowe too, and in the only lodging house next to the old roadhouse she paid for a room, and lay herself down in the clean sheets without even taking off her boots, the baby a warm softness on her chest, and together they slept and slept.

In the morning she bought a third-class ticket to Cambridge, and from there she and the baby continued south, into King’s Cross, into the smoke of darkest London.

***

The money she had stolen did not last. In Rotherhithe she gave out a story that her young husband had perished in a carting accident and that she was seeking employment. On Church Street she found work and lodging in a waterman’s pub alongside its owner and his wife, and was happy for a time. She did not mind the hard work, the scrubbing of the floors, the stacking of jars, the weighing and sifting of flour and sugar from the barrels. She even found she had a good head for sums. And on Sundays she would take the baby all the way across Bermondsey to Battersea Park, to the long grass there, the Thames just visible through the haze, and together they would splash barefoot in the puddles and throw rocks at the geese while the wandering poor flickered like candlelight on the paths. She was almost showing by then and worried all the time, for she knew she was pregnant with her old employer’s child, but then one morning, crouched over the chamber pot, a fierce cramping took hold in her and something red and slick came out and, however much it hurt her, that was the end of that.

Then one murky night in June a woman stopped her in the street. The reek of the Thames was thick in the air. Eliza was working as a washergirl in Wapping by then, making barely enough to eat, she and the baby sleeping under a viaduct. Her shawl was ragged, her thin-boned hands blotched and red with sores. The woman who stopped her was huge, almost a giantess, with the shoulders of a wrestler and thick silver hair worn in a braid down her back. The woman’s eyes were small and black like the polished buttons on a good pair of boots. Her name, she said, was Brynt. She spoke with a broad, flat American accent. She said she knew she was a sight but Eliza and the baby should not be alarmed for who among them did not have some difference, hidden though it might be, and was that not the wonder of God’s hand in the world? She had worked sideshows for years, she knew the effect she could have on a person, but she followed the good Reverend Walker now at the Turk’s Head Theatre and forgive her for being forward but had Eliza yet been saved?

And when Eliza did not reply, only stared up unspeaking, that huge woman, Brynt, folded back the cowl to see the baby’s face, and Eliza felt a sudden dread, as if Marlowe might not be himself, might not be quite right, and she pulled him away. But it was just the baby, smiling sleepily up. That was when Eliza spied the tattoos covering the big woman’s hands, vanishing up into her sleeves, like a sailor just in from the East Indies. Creatures entwined, monstrous faces. There was ink on the woman’s throat too, as if her whole body might be colored.

“Don’t be afraid,” said Brynt.

But Eliza was not frightened; she just had not seen the like before.

Brynt led her through the fog down an alley and across a dripping court to a ramshackle theater leaning out over the muddy river. Inside, all was smoky, dim. The room was scarcely bigger than a railway carriage. She saw the good Reverend Walker in shirtsleeves and waistcoat stalking the little stage, candlelight playing on his face, as he called to a crowd of sailors and streetwalkers about the apocalypse to come, and when the preaching was done he began to peddle his elixirs and unguents and ointments. Later Eliza and the baby were taken to where he sat behind a curtain, toweling his forehead and throat, a thin man, in truth little bigger than a boy, but his hair was gray, his eyes were ancient and afire, and his soft fingers trembled as he unscrewed the lid of his laudanum.

“There’s but the one Book of Christ,” he said softly. He raised a bleary bloodshot stare. “But there’s as many kinds of Christian as there is folk who did ever walk this earth.”

He made a fist and then he opened his fingers wide.

“The many out of the one,” he whispered.

“The many out of the one,” Brynt repeated, like a prayer. “These two got nowhere to stay, Reverend.”

The reverend grunted, his eyes glazing over. It was as if he were alone, as if he had forgotten Eliza entirely. His lips were moving silently.

Brynt steered her away by the elbow. “He’s just tired now, is all,” she said. “But he likes you, honey. You and the baby both. You want someplace to sleep?”

They stayed. At first just for the night, and then through the day, and then until the next week. She liked the way Brynt was with the baby, and it was only Brynt and the reverend after all, Brynt handling the labor, the reverend mixing his elixirs in the creaking old theater, arguing with God through a closed door, as Brynt would say. Eliza had thought Brynt and the reverend lovers but soon she understood the reverend had no interest in women and when she saw this she felt at once a great relief. She handled the washing and the hauling and even some of the cooking, though Brynt made a face each night at the smell of the pot, and Eliza also swept out the hall and helped trim the stage candles and rebuilt the benches daily out of boards and bricks.

It was in October when two figures pushed their way into the theater, sweeping the rain from their chesterfields. The taller of the two ran a hand down his dripping beard, his eyes hidden under the brim of his hat. But she knew him all the same. It was the man who had hunted her with dogs, back in Suffolk. Her dead employer’s father.

She shrank at the curtain, willing herself to disappear. But she could not take her eyes from him, though she had imagined this moment, dreamed it so many times, woken in a sweat night after night. She watched, unable to move, as he walked the perimeter of the crowd, studying the faces, and it was like she was just waiting for him to find her. But he did not look her way. He met his companion again at the back of the theater and unbuttoned his chesterfield and withdrew a gold pocket watch on a chain as if he might be late for some appointment and then the two of them pushed their way back out into the murk of Wapping and Eliza, untouched, breathed again.

“Who were they, child?” Brynt asked later, in her low rumbling voice, the lamplight playing across her tattooed knuckles. “What did they do to you?”

But she could not say, could not tell her it was she who had done to them, could only clutch the baby close and shiver. She knew it was no coincidence, knew in that moment that he hunted her still, would hunt her for always. And all the good feeling she had felt, here, with the reverend and with Brynt, was gone. She could not stay, not with them. It would not be right.

But she didn’t leave, not at once. And then one gray morning, carrying the washing pail across Runyan’s Court, she was met by Brynt, who took from her big skirts a folded paper and handed it across. There was a drunk sleeping in the muck. Washing strung up on a line. Eliza opened the paper and saw her own likeness staring out.

It had come from an advertisement in a broadsheet. Notice of reward, for the apprehension of a murderess.

Eliza, who could not read, said only, “Is it me name on it?”

“Oh, honey,” said Brynt softly.

And Eliza told her then, told her everything, right there in that gloomy court. It came out halting at first and then in a terrible rush and she found as she spoke that it was a relief, she had not realized how hard it had been, keeping it secret. She told of the man in his nightshirt, the candle fire in his eyes, the hunger there, and the way it hurt and kept on hurting until he was finished, and how his hands had smelled of lotion and she had fumbled in pain for her dresser and felt… something, a sharpness under her fingers, and hit him with it, and only saw what she had done after she had pushed him off her. She told about the boxcar too and the lantern that was not a lantern and how the baby had looked at her that first night, and she even told about taking the banknotes from the dead mother, and the fine clothes off her stiffening body. And when she was done, she watched Brynt blow out her cheeks and sit heavily on an overturned pail with her big knees high and her belly rolling forward and her eyes crushed shut.

“Brynt?” she said, all at once afraid. “Is it a very large reward, what they’s offering?”

At that Brynt lifted her tattooed hands and stared from one to the other as if to descry some riddle there. “I could see it in you,” she said quietly, “the very first day I saw you there, on the street. I could see there was a something.”

“Is it a very large reward, Brynt?” she said again.

Brynt nodded.

“What do you aim to do? Will you tell the reverend?”

Brynt looked up. She shook her huge head slowly. “This world’s a big place, honey. There are some who think you run far enough, you can outrun anything. Even your mistakes.”

“Is—is that what you think?”

“Aw, I been running eighteen years now. You can’t outrun your own self.”

Eliza wiped at her eyes, ran the back of her wrist over her nose. “I didn’t mean to do it,” she whispered.

Brynt nodded at the paper in Eliza’s hand. She started to go, and then she stopped.

“Sometimes the bastards just plain deserve it,” she said fiercely.

Excerpted from Ordinary Monsters by J. M. Miro. Copyright © 2022 by Ides of March Creative Inc. Excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.